Introduction

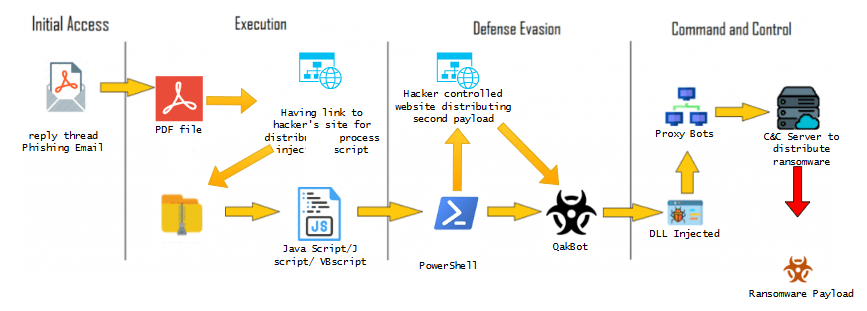

This case study documents a targeted malware campaign I investigated in 2023. The attack leveraged personalized phishing PDFs, unique download links, encrypted ZIP files, and an obfuscated script that ultimately delivered a Qakbot (Qbot) payload. All analysis was performed in a fully isolated personal research lab to ensure safe handling of artifacts.

Qakbot is a long‑standing malware family that has evolved from a banking trojan into a versatile loader capable of credential theft, persistence, and ransomware delivery. In this campaign, attackers relied on reply‑chain phishing and living off the land binaries (LOLBins) to bypass traditional defenses and blend malicious activity with legitimate system behavior.

Stage 1: Initial Access – Phishing PDFs

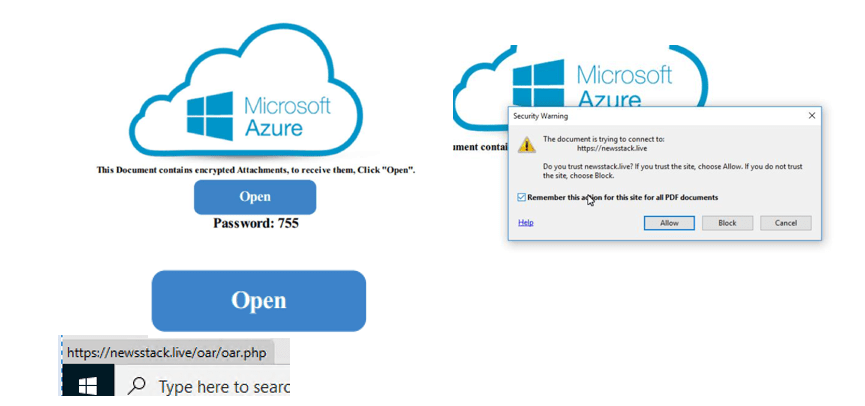

- Victims received PDF attachments that appeared to be part of legitimate business conversations.

- Each PDF contained:

- A fake Microsoft Azure‑themed message

- A visible password (“755”)

- A socially engineered lure (invoice, account update, etc.)

- An embedded URL hidden behind an “Open” button

- A unique two‑letter filename (e.g., , )

The PDF itself contained no exploit, allowing it to pass email gateway inspection. Its success relied entirely on social engineering.

Stage 2: ZIP Download

Clicking “Open” redirected the victim’s browser to:

- Newly registered domains

- Compromised legitimate websites (news, healthcare, etc.)

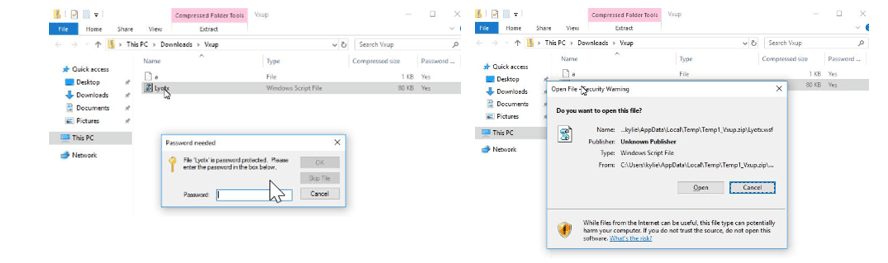

The victim was prompted to download a password‑protected ZIP file

The ZIP file was password-protected using standard archive encryption, which prevented email security tools from inspecting its contents. This technique is commonly used to bypass attachment scanning and sandbox detonation.

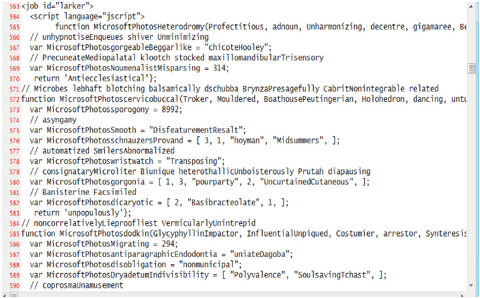

Stage 3: Script Execution

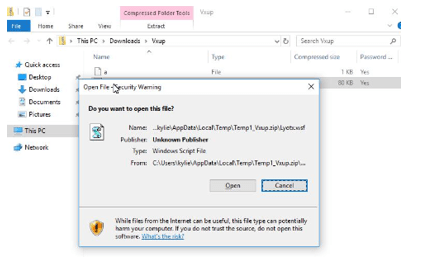

- Inside the ZIP was a Windows Script File (WSF).

- Double‑clicking launched

wscript.exe, which executed obfuscated JScript containing:

- Randomized variable names

- Encoded PowerShell launcher

- Multiple fallback URLs for payload retrieval

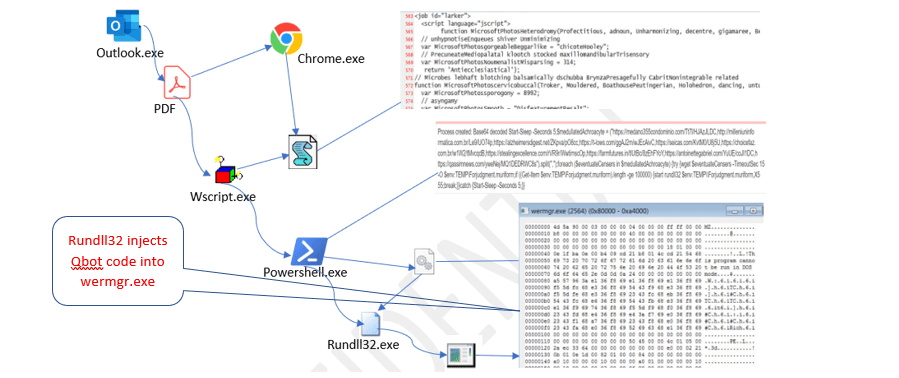

The JScript file didn’t contain readable PowerShell code. Instead, it embedded a Base64‑encoded command and launched PowerShell with it. Once decoded, that command handled the real work — downloading the DLL payload and executing it via rundll32.exe. This hand‑off technique hides the true logic and makes detection harder.

Stage 4: PowerShell Payload Staging

- The script invoked PowerShell with:

- Base64‑encoded commands (

-enc) - Long sleep loops (sandbox evasion)

- Error handling to retry multiple URLs

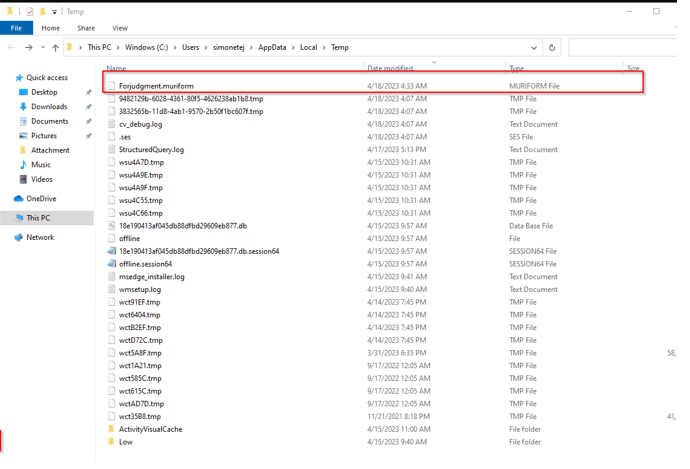

PowerShell downloaded a disguised DLL (forjudgment.muriform) into the Temp directory.

Stage 5: DLL Execution via Rundll32

- PowerShell invoked

rundll32.exeto load the DLL(forjudgment.muriform(which was a snowloader “Snowloader” is a term used by some security researchers for a specific component or function within the Qakbot malware that is responsible for downloading and installing the main malicious payload. It is not a separate, distinct malware strain but a part of the overall Qakbot operation. )). - The Snowloader DLL then injected Qakbot into

wermgr.exe(Windows Error Reporting Manager). - This technique, known as process hollowing, allowed Qakbot to masquerade as a legitimate system process.

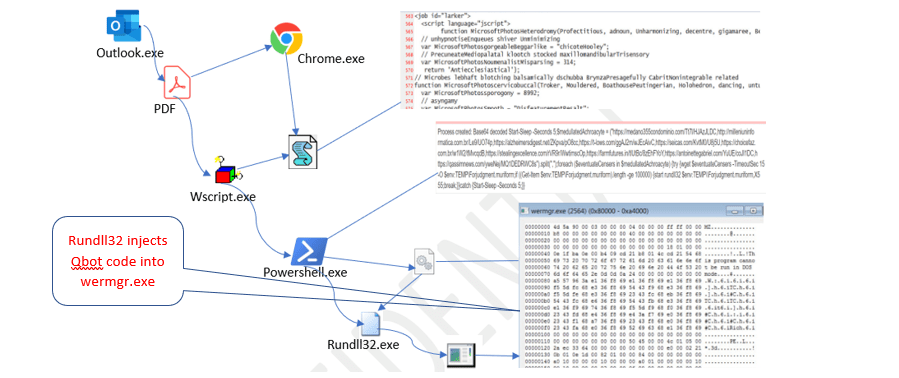

Process spawning summary:

wscript.exe→ launches PowerShell- PowerShell → drops disguised DLL (

forjudgment.muriform) - PowerShell → creates

rundll32.exeto run DLL - DLL → injects into

wermgr.exe/werfault.exe wermgr.exe→ initiates C2 traffic

Stage 6: Command‑and‑Control (C2) Activity

Once injected, wermgr.exe initiated outbound HTTPS connections to:

- Newly registered domains

- Compromised legitimate sites

- Hardcoded IP addresses (no DNS queries)

The malware also used:

ping.exefor sleep/delay- Encrypted traffic

- Multiple fallback C2 endpoints

Because the C2 servers were offline during analysis, Qakbot remained in a beaconing state and did not download additional modules. In a live environment, credential theft and ransomware deployment would typically follow.

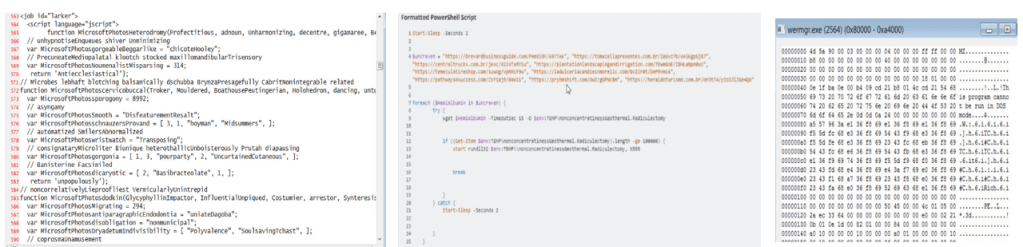

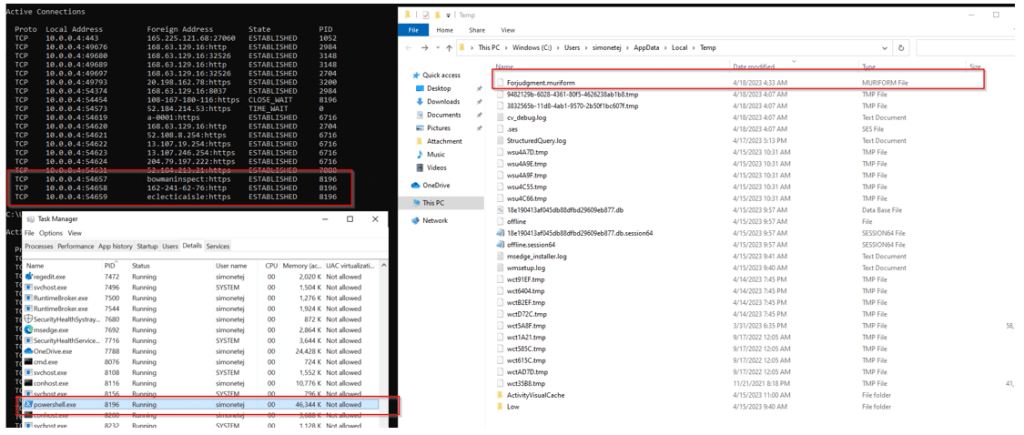

The screenshot below captures three forensic artifacts from the post-injection phase:

- Active outbound HTTPS connections from

wermgr.exeto attacker infrastructure - Running processes including

rundll32.exeandwermgr.exe, confirming stealthy execution - Disguised payloads in the Temp directory, including

.muriformfiles used by the loader

These indicators confirm that Qakbot successfully established C2 communication and was poised to receive additional modules — though in this lab environment, the servers were offline and no further payloads were delivered.

Key Takeaways

- Unique PDFs and URLs per user made correlation difficult

- Password‑protected ZIP files bypassed email security.

- Multiple fallback URLs ensured resilience.

- Payloads disguised with fake extensions reduced detection.

- Process injection hid malware inside legitimate Windows processes.

- Heavy reliance on LOLBins allowed Qakbot to blend in with normal activity.

Defensive Recommendations

Email Security

- Block execution of script files from ZIP archives.

- Detect reply‑chain phishing attempts.

Endpoint Detection

- Monitor for unusual use of

wscript.exe,powershell.exe, andrundll32.exe. - Flag encrypted PowerShell command lines.

- Inspect memory of LOLBins for injected code.

Network Controls

- Block newly registered domains at the perimeter.

- Detect long sleep loops and sandbox evasion behavior.

User Awareness

- Train users to spot fake Azure‑themed lures.

- Educate users about password‑protected ZIP phishing attacks.

Conclusion

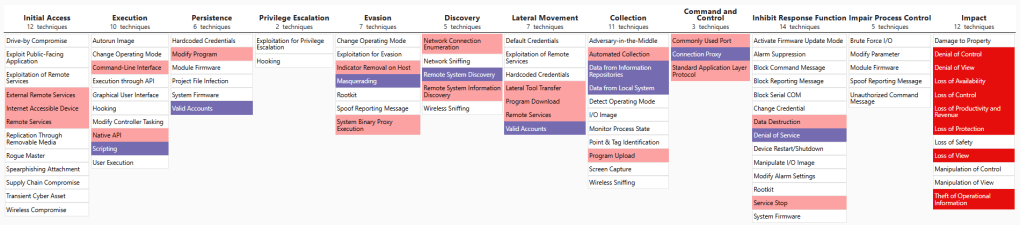

This case study illustrates how Qakbot infections unfold in carefully staged layers, exploiting both technical gaps and human trust. By mapping observed behaviors to MITRE ATT&CK techniques and highlighting defensive lessons, defenders can better anticipate adversary tactics and strengthen detection strategies.

Leave a comment